In this publication, we delve into the technique of wood finishing for Korean furniture during the Joseon Dynasty. To the best of our knowledge, there is a scarcity of studies in English on this subject, necessitating our reliance on publications in Korean. Our hypotheses are formulated based on a thorough examination of numerous pieces, the types of woods employed, the preservation methods employed, and the prevailing tastes of the era, which were significantly shaped by the lifestyle of the peninsula’s inhabitants.

Our initial focus is on the straightforward techniques that were commonly applied to the majority of furniture, excluding the lacquer finishes that were typically reserved for elite furniture, is the subject of another post. LINK: THE ART OF KOREAN LACQUER.

For more in-depth information on finishing techniques, please refer to the link provided alongside the furniture descriptions.

OIL ON WOOD.

The wood finishing process is founded on the research conducted by Edward Reynolds Wright and Man Sill Pai in their publication, “KOREAN FURNITURE: Elegance and Tradition.” The authors specify that there were two primary finishing stages: fillers or under-coatings, and the final coating.

FILLERS OR UNDER-COATINGS:

“1- Fillers and under-coatings: Most Korean sources agree on three substances used for this purpose.

-Clay (Hulk). This material was yellow, red or occasionally black. It was softened by mixing with water and sometimes vegetable oil and rubbed into the raw wood with a soft cloth. On most furniture. the clay coating was kept thin so as not to obscure the wood grain – it was to protect and darken the wood, not to leave a distinct color, and was rubbed off before becoming completely dry in order to achieve the desire result.

On implements receiving heavy wear “hulk” was thickly applied. The finish over this served to retain the clay’s color, usually obscuring the grain.

– Animal blood. Cow’s or pig’s blood was applied with a cloth to raw wood to protect and darken it. This staining method was used especially in remote rural areas and by the lower classes.

– Persimmon tannin is an effective protective undercoating, especially for lacquer. This substance is often used in Japan. Persimmon tannin is made from juice of the green fruit; a crude method was to rub with green persimmons.“

FINISHES:

– Perilla oil (tul Kirum). Over an undercoating of clay or animal blood, coats of perilla oil were rubbed into the surface with a soft cloth. This was by far the most popular way to finish Joseon dynasty furniture. Much furniture is said to have been finished in oil without undercoating. The result was quite similar as waxing furniture with natural bee wax.

– Smoking process. A method sometimes used for finishing small objects was to place them over smoke from rice straw that had been aged about one year. This causes the resin in the wood to come to the surface. This resin was then rubbed and spread over the wood with leaves or a cloth.“

LINK: THE BEAUTY OF PAULOWNIA WOOD.

The smoking process, sometimes employed for finishing small objects, involved placing them over the smoke from rice straw that had been aged for about a year. This would cause the resin of the wood to surface. The resin was then rubbed and spread over the wood using leaves or a cloth.

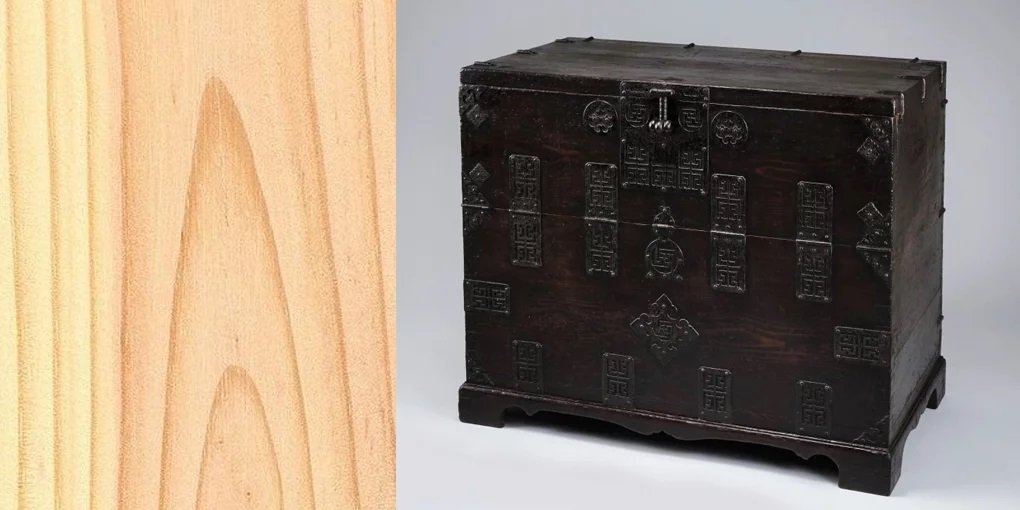

In the case of furniture made from paulownia wood, a burning method was also utilized. Due to its soft nature, paulownia wood is prone to staining and scratching.

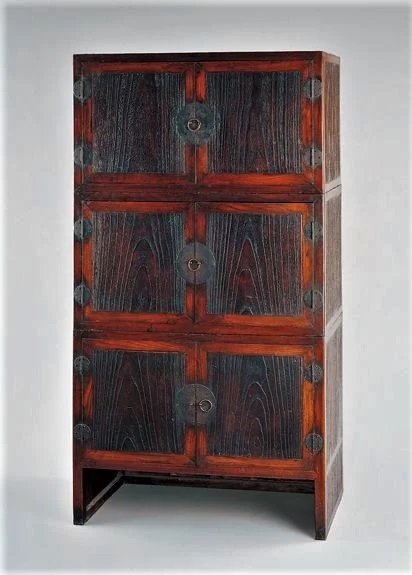

Dark colors dominated the finish of Joseon dynasty furniture, especially pieces destined for display in the men’s quarters. This large piece of furniture was built with paulownia wood that had first been charred to achieve the desired dark hue.

To address this issue, the “Nakdong Method” was employed. This process involved the removal of soft fibers by rubbing the wood’s surface with rice straw and then burning it, leaving behind only the hard grain. When this method was used, it revealed a rich, dark brownish-black color and brought out the beautiful grain of the wood. Subsequently, the surface was coated with natural oil, making the wood more resistant to fire, insects, and fungus. This technique has been known in Japan since the 18th century as “shou sugi ban” (焼杉板) and is primarily used on cedarwood.

For the final coating, a craftsman would gently apply oil from ginkgo nuts, walnuts, pine nuts, or sometimes beeswax onto the dry finish using a soft cloth. This not only provided further protection to the wood but also toned down the gloss.

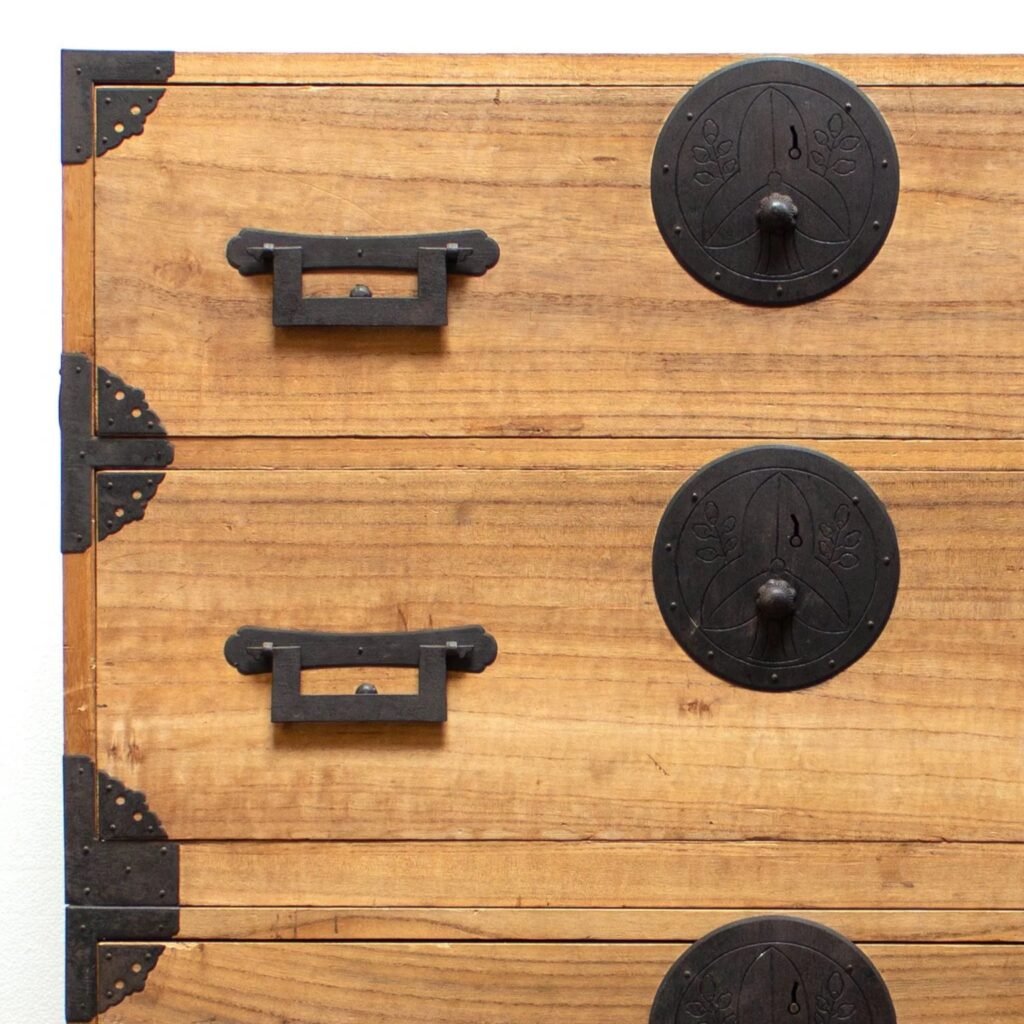

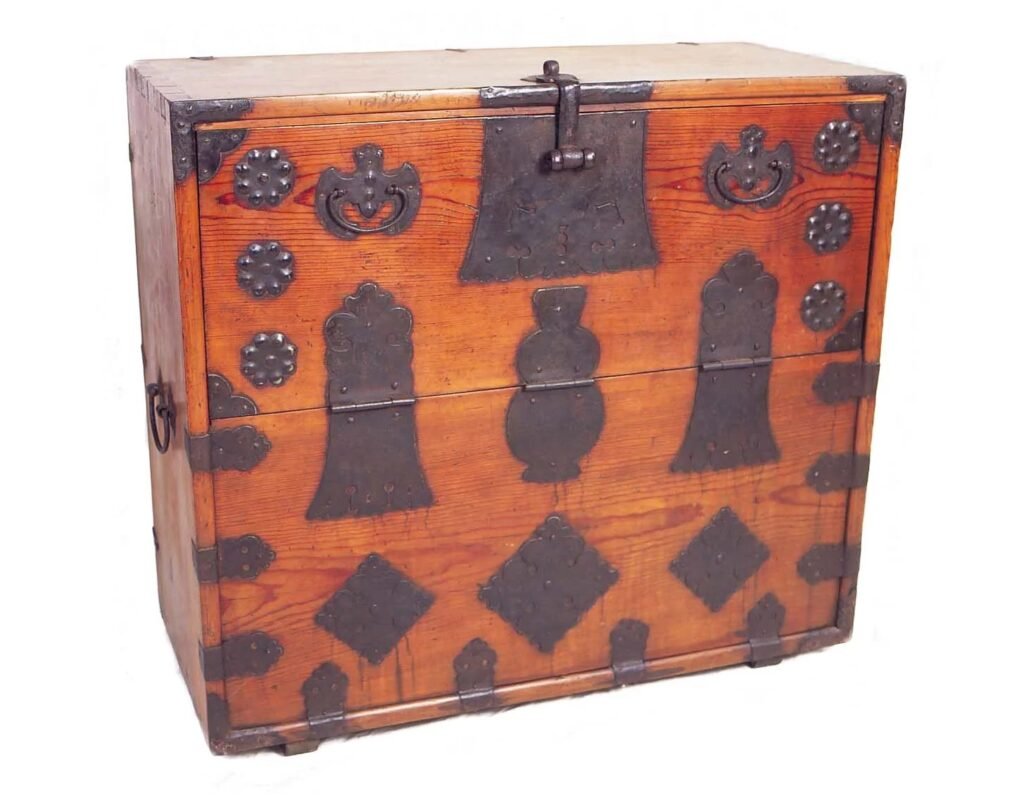

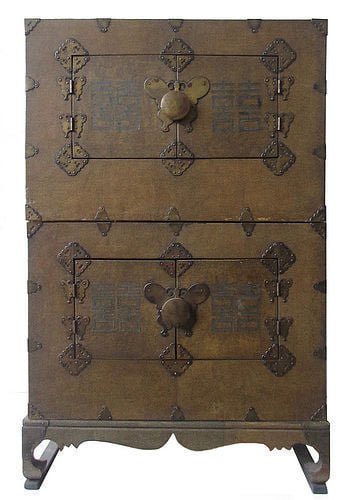

Once again, the bandaji, with its simple finish and absence of lacquer or other colors, serves as a perfect example for this study, as it was highly regarded in Korea. With the exception of furniture from Gangwon province in the east of the peninsula (photo left), which may have had a lighter color, most bandaji from other provinces were typically very dark in appearance, (photo right).

My question is, why?

To answer it, we need to consider two main assumptions. First, most chests were subdued and somber, in keeping with the sober decor expected in the surroundings of a gentleman scholar. The second reason is related to the effect of the finishing method used to protect the wood.

The wood surface was darkened by the process described above. This method was employed to prevent scratches or stains on the furniture’s surface, to make it waterproof, and to prolong its lifespan by preventing warping, cracking, and splintering.

Because of its poor grain a very dark stain was applied over the wood masking its grain. Abundant metalwork plates were used to decorate the front of those pieces.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION.

STAINING AND PAINTING TO MAKE WOODWORK LAST LONGER. By Yoon So-ra

The wood surface was colored and painted to protect it from contamination, cracking, warping, mold, insects, and to enhance its aesthetic appeal. Coloring was achieved by dyeing with substances like persimmon, gardenia, or ink, by generating smoke from burning pine branches, or by mixing and applying ocher powder, white clay powder, and evening liquor to the wood. For painting, various vegetable oils, such as walnut, pine nut, castor, perilla, and camellia oils, were used.

Korean carpentry typically employed wood that was naturally bright in color, but it was prone to staining and wear. Furthermore, the wood was used after drying, but its moisture content could fluctuate with changing weather conditions, leading to contraction and expansion, which in turn could result in cracking or warping. Additionally, wood was susceptible to various molds and insects, leading to corrosion. To safeguard and embellish woodcrafts from such threats, our ancestors painted the surface of objects with lacquer or oil.

Coloring involves the application of various materials to the surface of woodcraft to introduce color. Dyes made from substances like persimmon, gardenia, ink, etc., can be used. Alternatively, pine branches can be burned to create smoke, or a mixture of red clay powder, white clay powder, and “seokganju” (soil rich in iron oxide, producing a reddish hue) can be applied to the surface to achieve the desired color. The concentration can be adjusted during the application process.

Painting, on the other hand, serves the dual purpose of corrosion prevention and decoration by applying a paint that forms a protective film on the woodcraft’s surface. The primary materials used for painting are vegetable oils and lacquer. Vegetable oils, such as walnut, pine nut, castor, perilla, and camellia oils, are commonly employed. When these oils are applied to the woodcraft’s surface with a cloth, they create a thin protective film, enhancing the object’s appearance and making it shine beautifully.

Furthermore, if the lacquer obtained from the lacquer tree is diluted and applied to the surface of wooden crafts, a durable lacquer coating with a suitable sheen form, creating a protective film that deters insects and extends the usability of the furniture. Lacquer is not applied just once; rather, it is applied multiple times and allowed to dry for several days. Lacquer was primarily reserved for high-end products due to its intricate and costly manufacturing process, and its effects were so enduring that it was said to last for a thousand years if applied. Premium items were typically coated with raw lacquer, while everyday household items were painted with vegetable oil.

Another technique involves scorching the wood’s surface to slightly alter its color and reveal the natural wood pattern. This method was predominantly used for paulownia trees and rarely for pine trees. Initially, a heated iron is passed over the surface, followed by rubbing the wood grain with a straw to achieve a lustrous appearance. Lastly, the wood surface is rubbed with a natural oil. The result is a semi-gloss finish that closely resembles the wax finish commonly seen on Western furniture.

WOODCARVING

Woodcarving was relatively uncommon in Korean furniture when compared to their Chinese counterparts. The piece depicted in the photograph is part of the collection at the National Museum of Korea. It’s a three-level Jang, with intricately adorned front doors featuring openwork designs.

H. 114,5cm, W. 64,3cm, D. 37,3cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

HWAGAK TECHNIQUE.

LINK: HWAGAK

Collection National Museum of Korea.

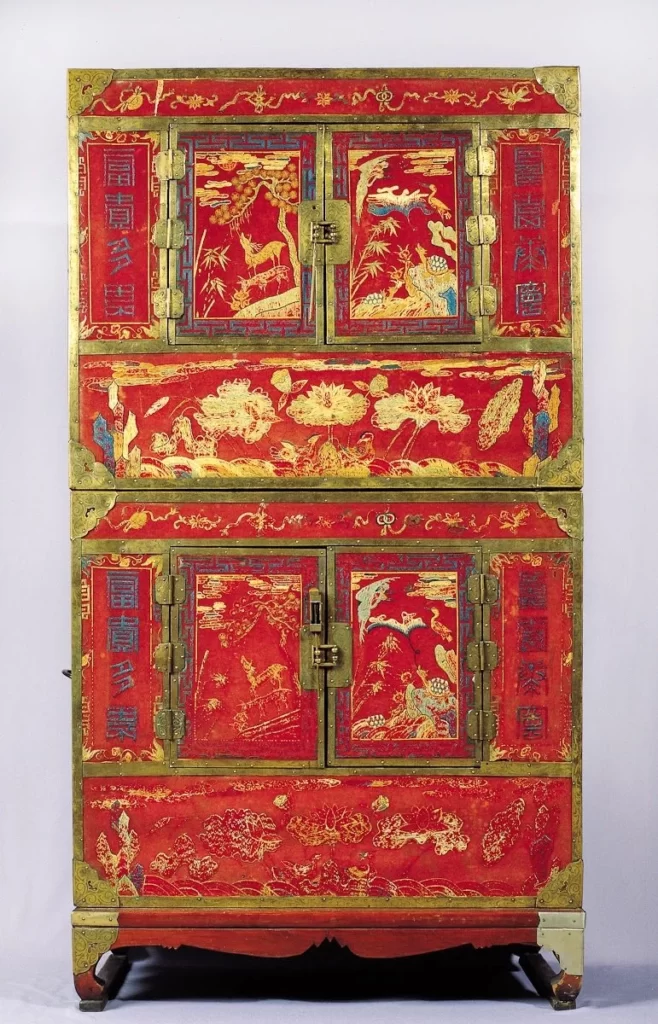

LACQUER.

LINK: THE ART OF KOREAN LACQUER

Pine wood, brass fittings, lacquer finish

H. 122cm, W. 69,8cm, D. 36,8cm. DATE 1800s.

Collection: WEISMAN ART MUSEUM – Minneapolis, MN, USA.

19th century. Collection of the National Museum of Korea.

According to Edward Reynolds Wright and Man Sill Pai in their excellent publication “Korean Furniture, Elegance and Tradition” red lacquer called “Chu-Ch’il ” in korean is refined lacquer mixed with either iron oxide or cinnabar pigments or a mixture of both. Colored lacquer was applied over an undercoating (often persimmon tannin). Items covered with such lacquer were intended for the court and nobles.

Collection: National Palace Museum of Korea.

GALUCHAT OR SHAGREEN INLAY.

LINK: LE GALUCHAT.

Antique shagreen stacking cabinet. Labelled 19th century.

H. 93cm, L. 61cm, D. 36cm.

Beige & green shagreen inlay signs of double happiness on the doors.

Private Collection.

PAPER.

LINK: THE USE OF PAPER ON KOREAN FURNITURE.

H. 82cm, W. 88cm, D. 48cm. Collection: ANTIKASIA.

H. 39,2cm, W. 66cm, D. 26,7cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

MOTHER-OF-PEARL INLAY

LINK: MAKING MOTHER-OF-PEARL LACQUERWARE

Lacquers made before the sixteenth century are extremely rare. Production from the Joseon period, which began after the 16th century, is considered less refined but more expressive, utilizing larger pieces of shell. Starting in the seventeenth century, mother-of-pearl fragments were no longer inserted into the lacquer layer but were instead glued directly onto the wooden base, which had previously been covered with fabric. While they employed similar techniques, utilized identical color schemes (primarily black and red), and featured similar motifs, Korean lacquers from this period differed from Chinese and Japanese lacquers in the sobriety of their composition and forms. These lacquers were typically used for aristocratic purposes, often found in the form of boxes. The compositions of the early period continued the use of repeated motifs but with a more spacious and ample design than before. After the reconstruction in the seventeenth century, they often featured large symmetrical effects or were centered around a prominent form, resulting in a clear composition where the background played a significant role.

REF: Wikipedia.

19th century, Wood, lacquer, abalone shell, metal.

This hat box, entirely encrusted with pieces of abalone shell, was used to store a man’s inner hat, or “tanggeon“. Korean craftspeople used a special technique to create such objects. First a wooden box was coated with several layers of lacquer, onto which pieces of abalone shell were affixed. They then continued to coat the box with lacquer until the shell was completely covered. After the lacquer dried, they laboriously polished the surface with charcoal until the iridescent shell was revealed. Typical of Korean style, the mother-of-pearl is broken and reassembled in the manner seen here.

Collection: MIA. The Minneapolis Institute of Art. USA.

H. 25,3cm, W. 57,3cm, D. 28cm. Collection National Museum of Korea.

Early 20th century

Late Joseon Dynasty.

Collection: The MET. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

TORTOISE SHELL.

FABRIC OR EMBROISERY ON FURNITURE.

LINK: THE PAST & PRESENT OF KOREAN EMBROIDERY.

This embroidered chest is said to have been produced for the garye (wedding) of queen Sunwon, who was the wife of Sunjo, the 23rd king of the Joseon dynasty. The ten traditional symbols of longevity were embroidered on the door and on the lower part of the door, lotus flower and mandarin duck designs were embroidered so as to wish for the couple to be happy and bear many children.

Collection: Sookmyung Women’s University Museum, Seoul. Korea.

METAL INLAY.

LINK: METAL INLAY, AN OLD KOREAN CRAFT.

철제 은입사 감실 (鐵製銀入絲龕室)

Late 1800s. Iron inlaid with silver and copper decoration

H. 35cm, W. 30cm, D. 14 cm. Collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

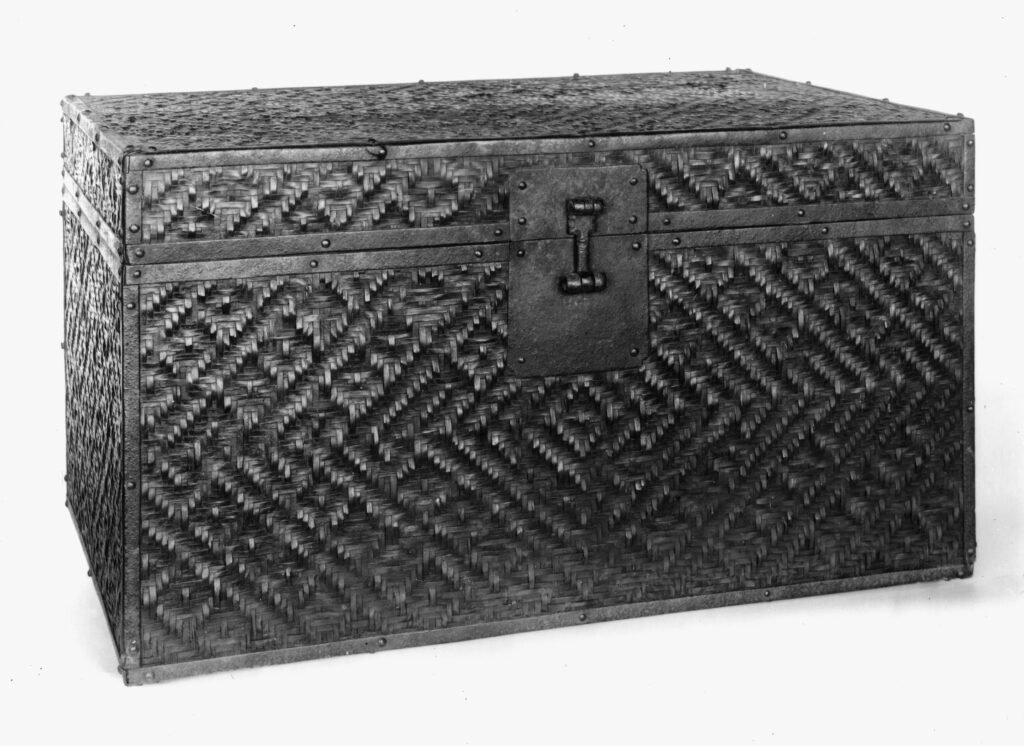

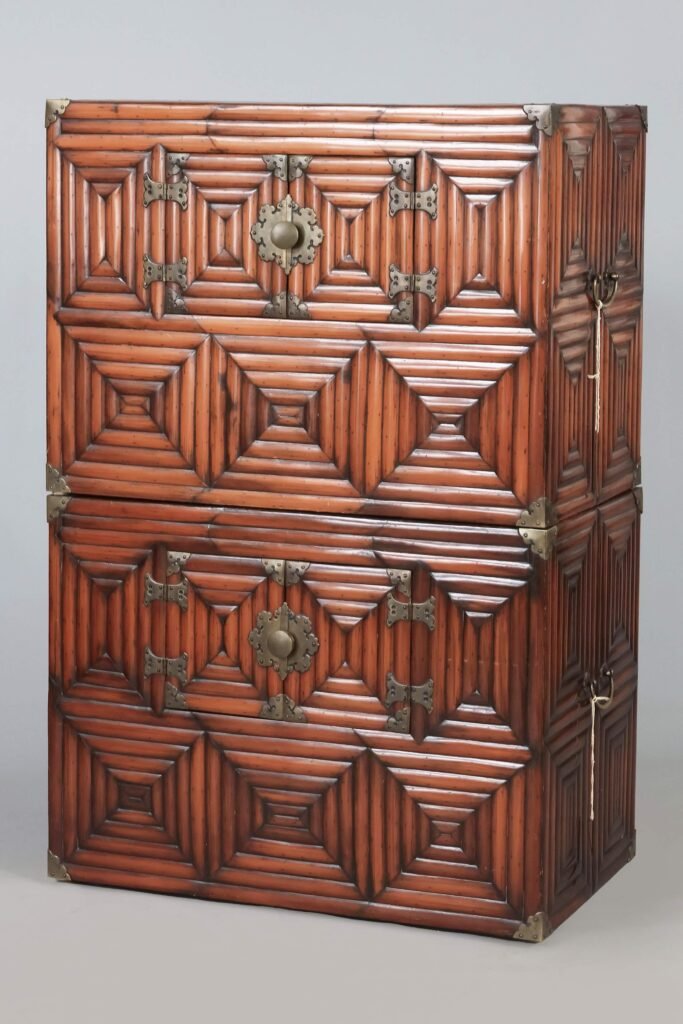

BAMBOO.

Bamboo (대나무 – “Daenamu“): While not a wood species, bamboo was an essential material for making various household items like screens, mats, and baskets. Bamboo groves were common in Korea, especially in the southern regions.

H. 180,5cm, W. 108,3cm, D. 62,3cm. Collection National Museum of Korea.

Wood covered with bamboo. H. 42,9cm, W. 80,2cm, D. 40,2cm. Collection National Museum of Korea.

Auction: Christie’s March 28, 2006.

Assembled with two open shelves above two shallow rectangular drawers and two large lower shelves covered by hinged doors carved with characters for good luck, the surfaces applied with rows of slit bamboo with reddish brown finish

48½ x 22¼ x 12¼in. (123.3 x 56.5 x 31.1cm.)

WOOD COVERED WITH LEATHER.

H. 17,5cm, W. 32,2cm, D. 16,5cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

WOOD COVERED WITH STONE.