The Bandaji, known as a blanket chest in the West, is likely the most prevalent type of Korean clothing chest from the Joseon Dynasty. Its front is divided into two parts, with the upper half designed to open and close. The name “Bandaji“ is derived from the Korean words “Ban,” meaning “half,” and “Daji,” meaning “closing,” highlighting the unique feature of only half of it being accessible. In certain regions, it is also referred to as “Apdaji,” where “Ap” signifies “forward,” due to the forward opening and closing motion.

The structure of Bandaji can be categorized into two main components: the body and the legs. The body consists of a top panel, front board, side board, bottom board, and door panel, all reinforced by metal plates once assembled. While the interior of this structure is predominantly empty, it can be customized based on the user’s requirements, with options to add drawers or shelves. To ensure robustness and functionality, each wood connection is securely reinforced with metal corner fittings.

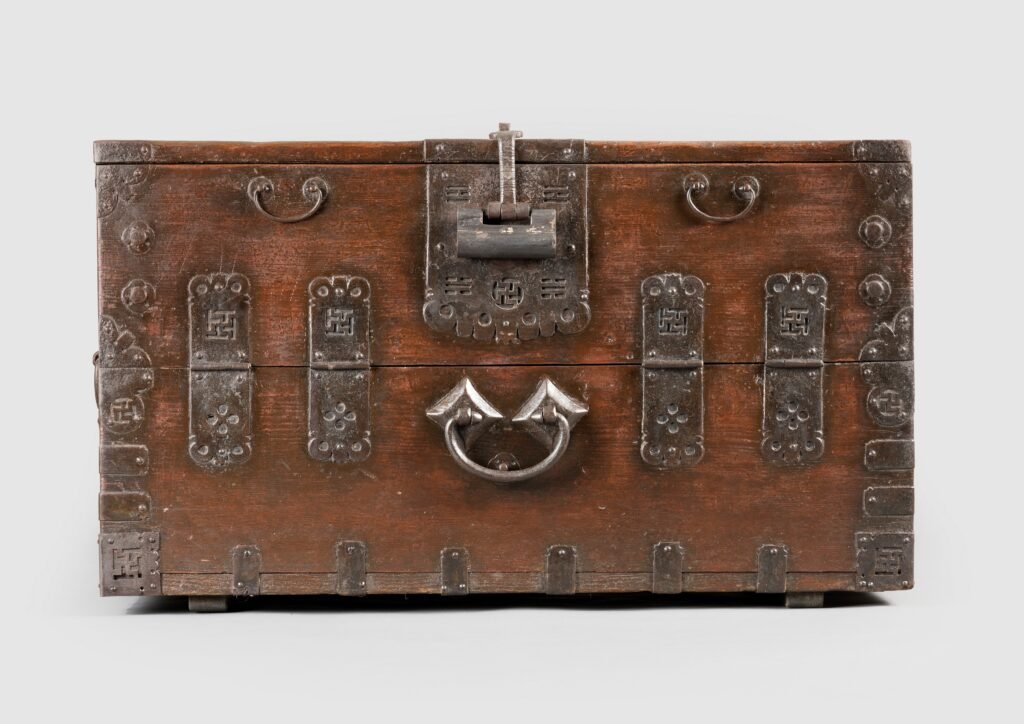

The metalwork is an important factor to highlight not only the functional aspects of Bandaji, but also the aesthetic aspects. Therefore, unlike those used for other types of furniture, the metalwork for Bandaji has various shapes with a meaning of decoration. It is difficult to find a Bandaji of the same size and shape because craftsmen’s skills and regional characteristics allow the design to be varied.

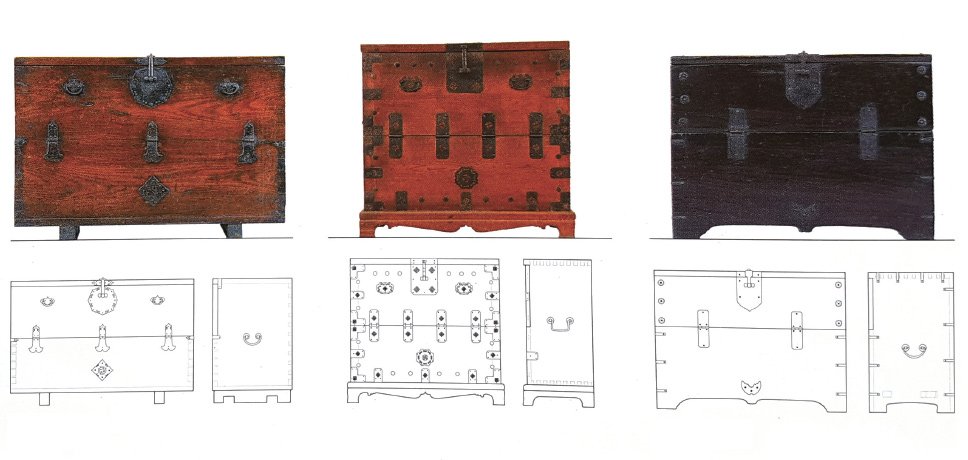

The shape of Bandaji in the Joseon dynasty was settled after going through repetitive modifications and transformations. It was not made on the basis of certain specifications, so this paper intends to systematically analyze the structure and the manufacturing techniques based on changes in shape. Specifically, we studied the form of the front side, the structure of door panels, the form of the legs, and the internal structure.

Design of front side.

The front side of a Bandaji can be classified into various types: general, extended, framed, partitioned, and complex.

The general type is the most popular, with its front side composed of a front board and a door panel, both made of planks.

Collection: The Portland Art Museum, USA.

In the case of the extended type, the ceiling board slightly protrudes more than the side boards, resembling the upper part of a closet.

Collection: National Museum Korea

In other cases, the top tray had raised ends. It was also used to store documents, including scrolls. These unfolded scrolls could be consulted on top of the furniture without worrying that they might be damaged by falling.

For the framed type, the front board and door panel are inserted into each board of the body, creating a framed appearance. Unlike other Bandaji types, where the front view hides side boards, top board, and bottom board, the framed type exposes a section of the body, resembling a frame. This design was very popular in Gangwon Do province.

Collection: Sokcho city Museum, Korea,

In the partitioned type, the structure is similar to the front of a cabinet as the front panel is divided into a wooden frame and inserted panels. Due to their large size, the split type is commonly found in Bandaji from the Northern provinces, such as Pyongyang Bandaji and the northern areas of Gyeonggi Do province.

Built from zelkova with burlwood panels, this piece is decorated with fine yellow brass fittings. The top three drawers feature bat-shaped hinges, while the opening section, which doesn’t extend all the way, is maintained by swallowtail hinges and a round lock plate. At the center bottom, a decorative plate is adorned with the “Manja” (Swastika) pattern.

Collection: Andong City Folk Museum, Gyeongsang Do province.

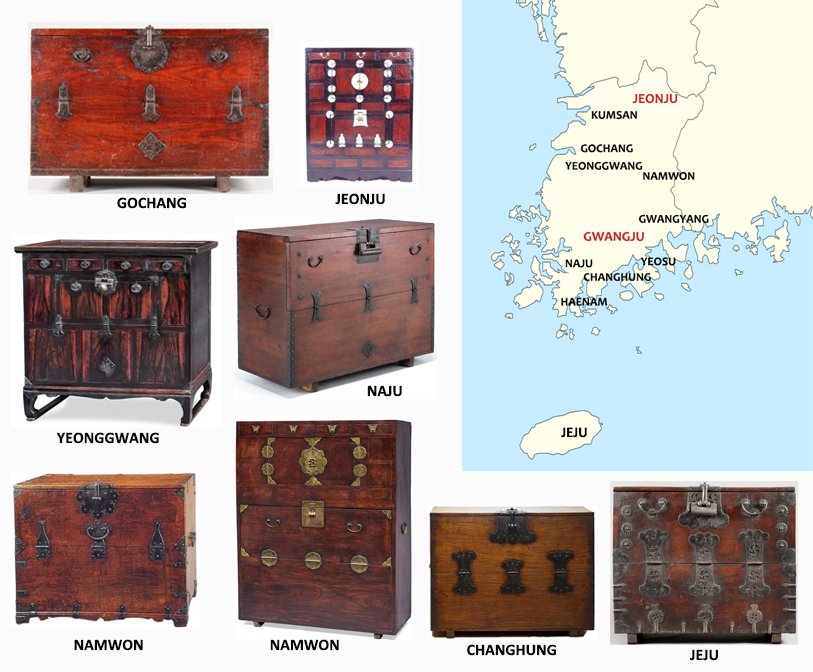

The complex type is a fusion of Bandaji and cabinet. These bandaji are typically owned by the wealthy and can be found in Gyeonggi-do, Gyeongsang-do, and Jeolla-do provinces. The best known being Jeongju bandaji from Jeolla Do province.

Collection: National Folk Museum of Korea.

Structure of door panel.

The structure of the door panel is closely related to the size of Bandaji. Different manufacturing techniques are employed for larger Bandaji to prevent distortion of the door panel. Based on structural considerations, the door panel is classified into plank type and frame type (two-side reinforced or four-side reinforced). The plank type is constructed with 20 to 30 mm thick boards and is the most commonly found type.

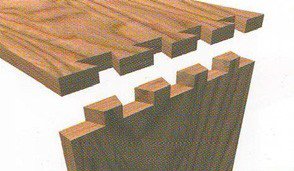

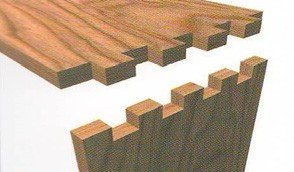

The frame type of the door panel was developed for larger Bandaji, aiming to prevent distortion of the door panel while also considering aesthetic aspects. Boards are added to two or four sides of the door panel, and various joining techniques are employed for this type, such as edge-bonding, dovetailing, halving, and clamping.

Form of legs.

The legs of a bandaji serve both functional and decorative purposes, taking into account ventilation between the body and the floor in the Korean under-floor heating system. These factors result in various leg shapes. The legs are categorized into three types: Jokdae type, Madae type, and monolithic type. The Jokdae type is the most common, where square or rectangular timber legs are attached to the body. The Madae type is typically found in closets or clothes-boxes, where the legs and body are separable, though sometimes the legs are fixed to the body. The monolithic type involves integrating four boards (front, back, left, and right) with the legs. In this design, the side boards, front board, and back board extend to the floor, serving as the legs. Alternatively, both side boards may be lengthened to function as legs.

Internal structure.

The internal structure is adaptable based on the user’s application and the contents to be stored. It is classified into four types: empty-type, shelf-type, drawer-type, and papeterie-type. The empty-type is the most common, with no internal compartments in the bandaji. On the other hand, the shelf-type, drawer-type, and papeterie-type are primarily used in rooms to store valuables, documents, or other small items.

The shelf-type features one or two shelves on the top of the interior. The drawer-type has a drawer either at the top or the lower part below the shelf. The papeterie-type combines both a shelf and a drawer and is often used in detached living rooms to store important documents, items, or stationery. This type is frequently found in the Jeollado region.

Internal structure: Shelf type.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Internal structure: Drawer type.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Internal structure: Papeterie type.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

Main joinery methods on bandaji.

Dovetail joints are commonly used in box construction, such as in the making of bandaji. The finger joint is another method employed to join two pieces of wood at right angles to each other. It is similar to a dovetail joint, with the distinction that the wooden pins are cut square rather than at an angle. The lap joint, also known as a rabbeted joint, is another technique utilized for joining two pieces of wood by overlapping them.

Materials.

Building the Bandaji required solid hardwoods. Pine, elm, zelkova or linden were the most important species. Occasionally, ash, pear and, more rarely, paulownia were used for certain parts.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Finishes.

In general, Korean furniture was traditionally finished with an application of perilla oil. This oil penetrated the wood, enhancing its natural grain and color, typically resulting in a satin or matte sheen.

The bandaji, considered first and foremost as a purely utilitarian piece of furniture, was devoid of any excessive decoration apart from the abundance of metal hinges in the northern part of the peninsula. There was no lacquer or inlay. However, we did find one exceptional lacquered piece.

Photos (3) above: A black lacquer bandaji adorned with mother-of-pearl inlay.

Bandaji, or blanket chests, were seldom coated in lacquer, unlike multi-tiered furniture like the “Jang.” The lacquer finish, mother-of-pearl decorations, and the incorporation of yellow brass suggest that this piece, originating from Gyeonggi province, might have been owned by a nobleman closely associated with the royal court.

The vermilion hue of the base was typically reserved for the royal court, though its usage began to proliferate toward the end of the Joseon dynasty.

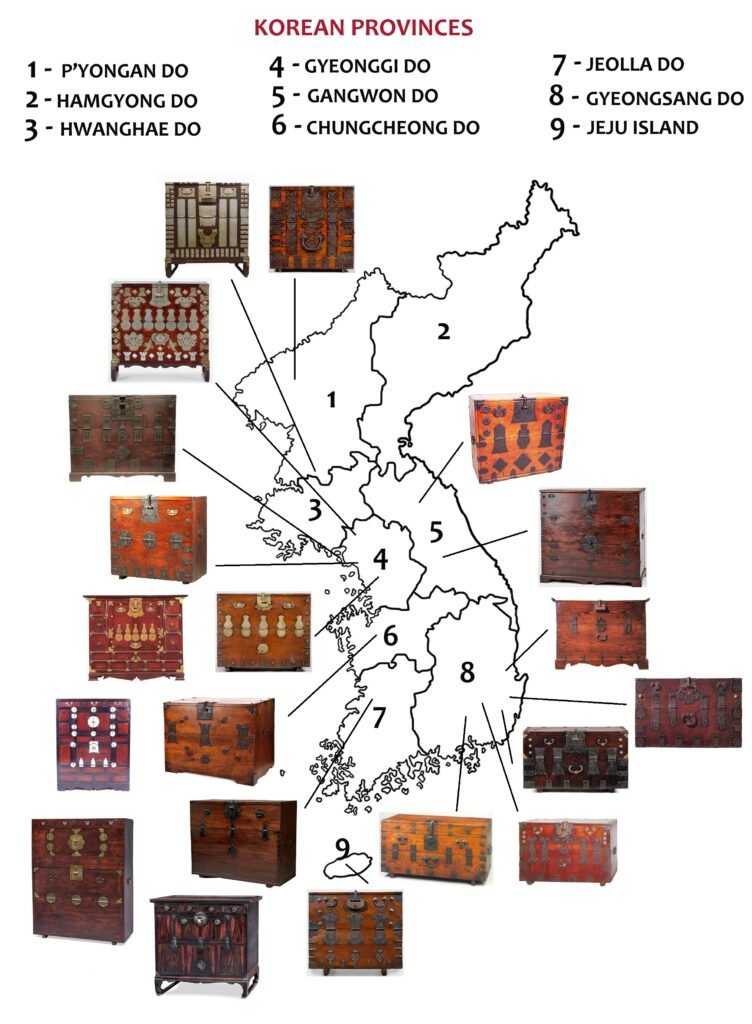

REGIONAL DIFFERENCES.

Despite the relatively small size of the Korean territory and its very low population density during the Joseon dynasty, one might assume that the style of furniture, in general, was highly homogenous.

However, this was not the case, and in this study, we will attempt to demonstrate this and determine the main reasons for these variations.

These differences in design and decoration are less pronounced than those of their Japanese and Chinese neighbors. Nevertheless, when examining specific pieces of furniture, as shown in the image below, one can discern variations in shape, size, and decorative motifs.

The investigation into the descriptions of pieces found in the eight provinces of the Korean peninsula has been the subject of several publications on this site:

– GYEONGSANG DO BANDAJI- 경상도 반닫이

– GYEONGGI DO BANDAJI – 경기도 반닫이

– CHUNGCHEONG DO BANDAJI – 충청도 반닫이

– GANGWON DO BANDAJI – 강원도 반닫이

– FURNITURE FROM THE NORTHERN PROVINCES

There are indeed regional differences in the design, decoration, and usage of bandaji in Korea, and these differences can be explained by several factors:

Architecture & home design: The layout and style of homes and interiors can vary by region, influencing the size and shape of bandaji to fit within the available space and complement the overall aesthetic.

Materials and Availability: The type of wood and materials available in a particular region can influence the design of bandaji. Different regions may have access to specific types of wood or resources that are more suitable for crafting bandaji, leading to variations in their construction. The availability of local materials played a crucial role in the design and construction of bandaji. Regions with abundant wood resources may have created larger and more intricate chests, while those with limited resources might have developed smaller, simpler designs.

Climate and Environment: Climate and environmental conditions can also play a role in bandaji design. For instance, regions with more extreme temperatures or humidity levels may design bandaji with features that protect the contents from these environmental factors. Bandaji from coastal areas might differ from those in mountainous regions due to the influence of saltwater and humidity.

Functional Needs: The way bandaji are used can vary by region. Some regions may use them primarily for clothing storage, while others might repurpose them for other uses, such as books and documents storage.

Socioeconomic Factors: Socioeconomic conditions and social customs can also influence the design and use of bandaji. Wealthier regions or families may have more elaborate and ornate bandaji, while those with fewer resources may have simpler, utilitarian versions.

In summary, the regional differences in Korean bandaji can be explained by a combination of historical, cultural, environmental, artistic, and socioeconomic factors. These chests are not only functional but also cultural artifacts that reflect the rich diversity of Korean heritage and craftsmanship.

PYONGAN DO BANDAJI – 평안도 반닫이

Pyongan Do has held a central role in Korea’s ancient national history since the time of Dangun, encompassing Gija Joseon and Goguryeo. The city of Pyongyang also served as the administrative base for the northern region since the Goryeo Dynasty. As a result, it stands as the oldest city in Korea, symbolizing the northern region as a hub for economy, culture, and transportation. The name Pyongyang is derived from the flat terrain surrounding the city.

The city experiences an inland climate, as described in the Sejong Annals of Geography (世宗實錄地理志): “The land is less fertile and drier, with a very cold climate.” During winter, the northwest monsoon brings cold temperatures, while in summer, it exhibits a hot and dry continental climate.

Due to the harsh winter conditions, there was a need to enlarge the size of the bandaji mainly to accommodate thicker clothing for insulation. As a result, it has become the largest among local bandaji and its internal structure often includes storage space for thick clothing, similar to the Pakchon bandaji, sometimes with attached drawers.

The wood used in construction is predominantly walnut, linden, and pine to ensure durability and thickness. Those timbers were also widely available in this part of the peninsula.

While Pyongyang’s metalwork material differs from that of Pakchon, the metal plates in Pyongyang are distinctly unique compared to those in other regions, owing to the evolution of their metalworking culture. “The fittings cover a significant portion of the chest’s front and are, in most cases, crafted from white brass.

Door plates in this region are often crafted using door edges rather than full plates, which helps prevent large door plates from becoming distorted.

As a distinguishing feature of these two regions, Pakchon Bandaji serves as an excellent example of advanced metalwork technology, featuring intricate openwork cast iron fittings and prominently showcasing delicate engraved patterns.

The average size of the Bandaji in the Pyongan-do area, classified into Pakchon and Pyongyang Bandaji, measures H. 91,7cm, W. 92cm, D. 45,8cm.

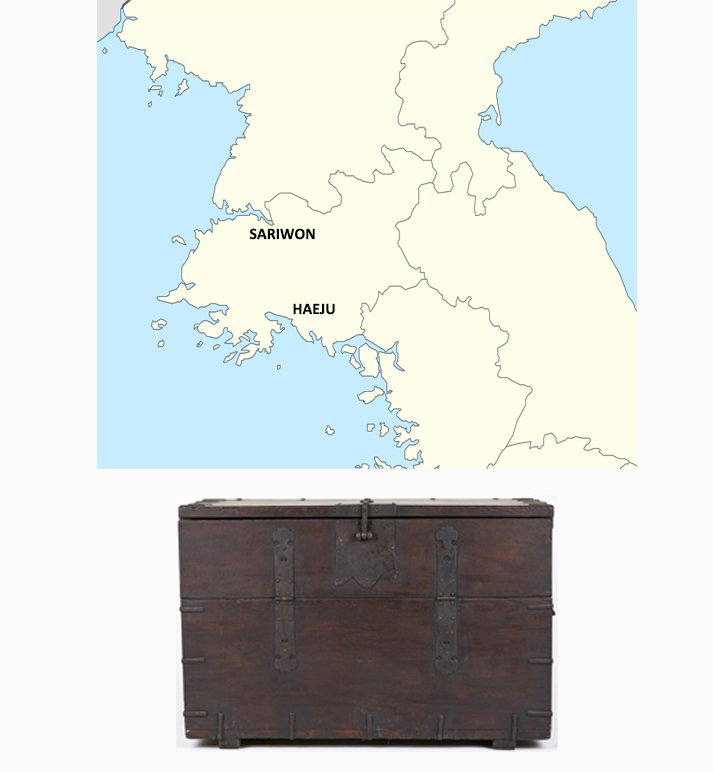

HWANGHAE DO BANDAJI – 황해도 반닫이

Hwanghae Do Bandaji. Regrettably, we lack information about the bandaji in this province. We were only able to consult a single photographic document, which depicts a very simple bandaji without excessive decoration. Crafted from pine, the front is adorned with wrought-iron hinges showcasing a flower and swallowtail motif.

Dimension of this Bandaji is: H. 66,7cm, W. 99,3cm, D. 51,3cm.

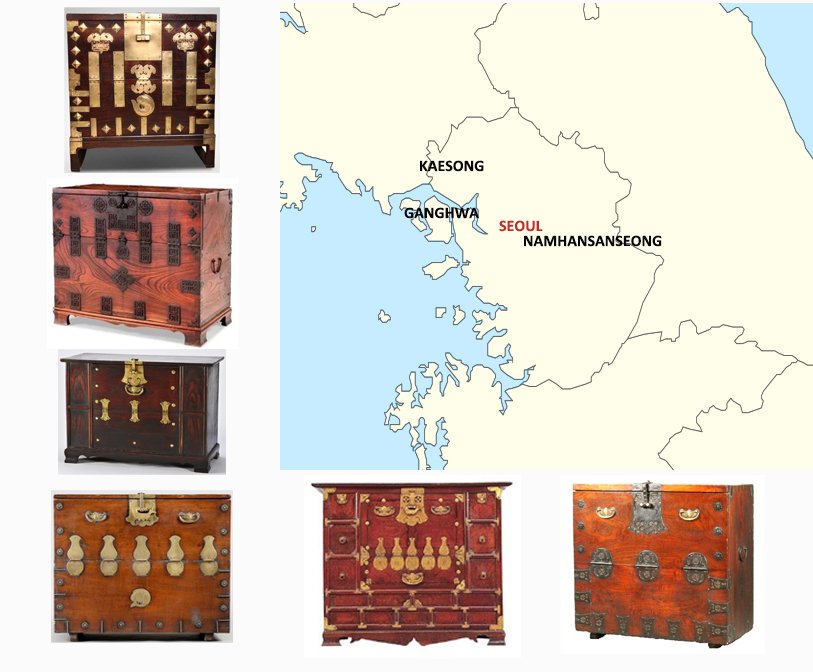

GYEONGGI DO BANDAJI – 경기도 반닫이

Gyeonggi-do Bandaji. Gyeonggi-do, located in the western part of central Korea, boasts a history of settlement dating back to prehistoric times, thanks to the fertile plains along the Han River. It served as a prominent administrative center, including Hanseong, the capital of the Gyeonggi region during the late Joseon Dynasty. Positioned at the country’s heart, it enjoys excellent conditions for waterway transportation, particularly along the Han River. Furthermore, due to its convenient trade connections with China, Gyeonggi-do has a long history of foreign trade and commerce. This early urban development has resulted in distinctive regional characteristics in Bandaji, setting it apart from other areas, with Ganghwa being one of its notable types. Bandaji can be divided into Gyeonggi Bandaji, Namhansanseong Bandaji, Ganghwa Bandaji and Kaesong Bandaji. Notably, the reinforced half-door is crafted from wood of a specific thickness, sturdy cast iron, and features intricate and uniform openwork patterns.

The average dimensions of bandaji in the Gyeonggi-do region measure H. 84,4cm, W. 91,8cm, D. 46,3cm.

GANGWON DO BANDAJI – 강원도 반닫이

Gangwon-do, situated in the northeastern mid-region of the Korean Peninsula, experiences colder temperatures due to its higher altitude compared to the Gyeonggi region at the same latitude.

The primary wood used in the region was predominantly pine, and most of the furniture legs were unattached.

Gangwon-do is characterized by its mountainous terrain, making transportation inconvenient and external trade challenging.

The metalwork in the region is notably thinner and appears less mature when compared to other areas. It is characterized by its large size and relative thinness.

The front background of the furniture is intricately engraved with patterns such as swallowtail shapes and constellations. The extended base of the furniture has an L-shaped design with three hinges, featuring a gourd hinge in the center and larger hinges for figurative fire designs attached to the left and right sides. The average size of a Bandaji in Gangwon-do measures H. 75,7cm, W. 84,8cm, D. 39,7cm. which is smaller than those found in Pyongan-do and Gyeonggi-do provinces.

CHUNGCHEONG DO BANDAJI – 충청도 반닫이

JEOLLA DO BANDAJI – 전라도 반닫이

GYEONGSANG DO BANDAJI- 경상도 반닫이

APPENDIX.

1- REGIONAL CHARACTERISTICS

| PROVINCE | DIMENSION & DESIGN | WOODS | FITTINGS |

| PYONGAN DO | Large – General type- Legs Jokdae & Madae types. | Linden, Pine | Type 1: “Sung Sun I” style. Numerous cast iron with elaborate openwork Type 2: “Pyongyang” style. Numerous white brass covering the front part |

| HWANGHAE DO | Large – General type – | Linden, Pine | Cast iron |

| GYEONGGI DO | Medium to large – General & complex types | Red pine, elm, zelkova, ash | Type 1: “Ganghwa” style. Cast thick iron. Intricate designs. |

| GANGWON DO | Medium to large – Framed type | Red pine, pine | Cast iron |

| CHUNGCHEONG DO | Medium – General type | Pine | Cast iron |

| JEOLLA DO | Large – General type – Legs Jokdae type | Elm, red pine | Cast iron |

| GYEONGSANG DO | Small, Low & wide – General type – | Elm, zelkova, red pine | Cast iron. Intricate designs. |

2 -RICE CHEST, BANDAJI OR COIN CHEST?

Many people confuse three main types of furniture: the rice chest, the bandaji, and the coin chest. This illustration should make it easier to distinguish between them.

[…] BANDAJI – 반닫이 : Sometimes also called ABDAJI. The bandaji, is the most essential type of furniture for a Joseon dynasty household, was produced throughout the Korean peninsula, and each region developed its own unique style. […]

[…] the various pieces of Korean clothing chests, the Bandaji was the most diverse in terms of style. It was designed for storing clothes inside, with folded […]