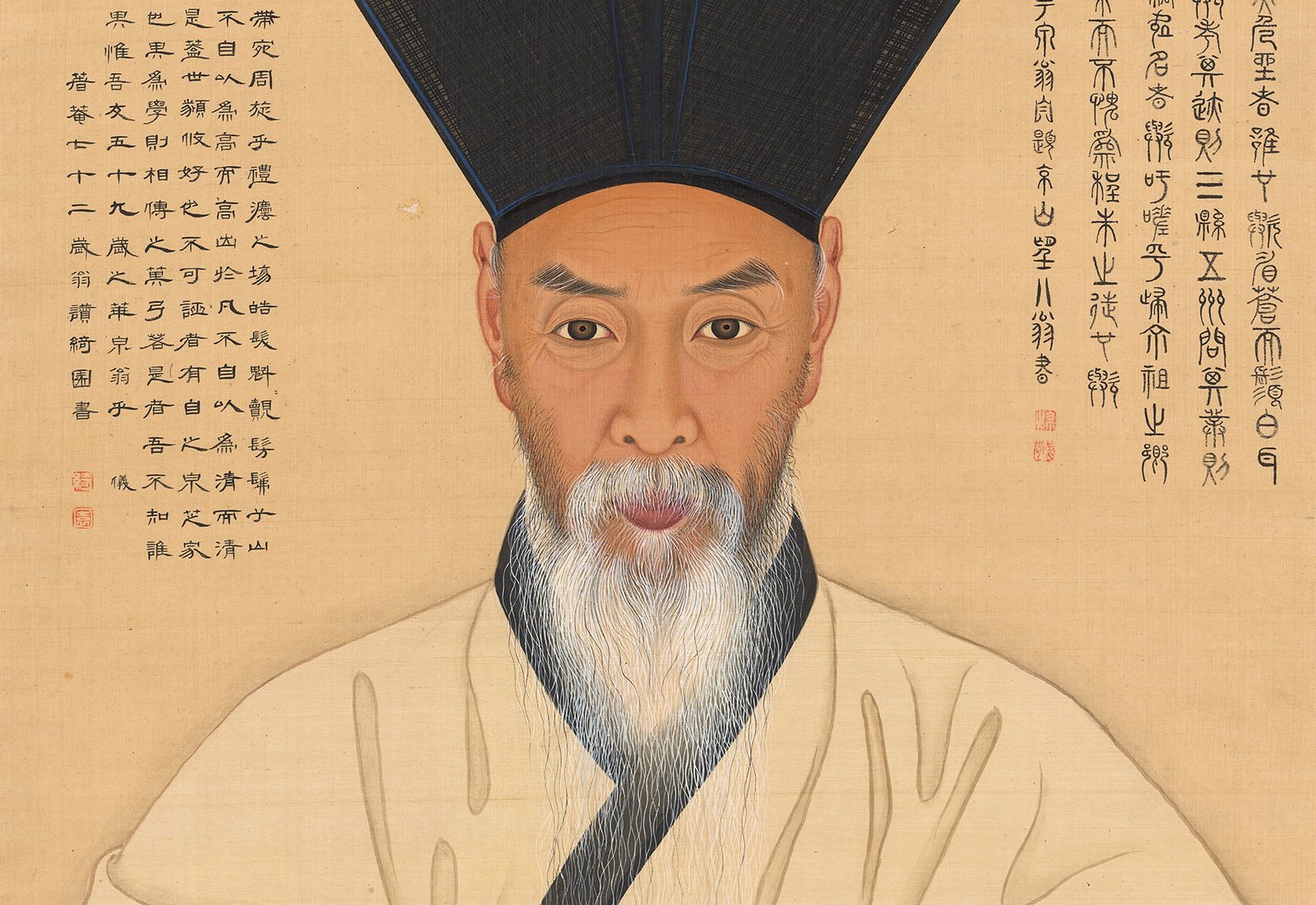

Featured photo: The portrait of Yi Chae depicts the renowned scholar of the late Joseon period, clad in a pointed dongpagwan hat and a scholar’s robe, or “simui” (a white hemp robe with black trim). In this half-body portrayal, Yi Chae gazes directly from the canvas while maintaining impeccable posture. It is part of the collection at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul.

Elegant, precise, and understated, these adjectives aptly characterize the furnishings of classical scholars from the Joseon Dynasty.

Scholar’s chests in Korea are also referred to as “Sarangbang” furniture. The term “Sarangbang” (사랑방, 舍廊房) denotes a room found in a traditional Korean house “Hanok“. “Sarangbang” served as a men’s room, primarily used for studying, writing poetry, and leisure activities.

This type of furniture includes open stationery chests, book chests, writing tables, bookshelves, and paper-filing cabinets.

STATIONERY CHESTS.

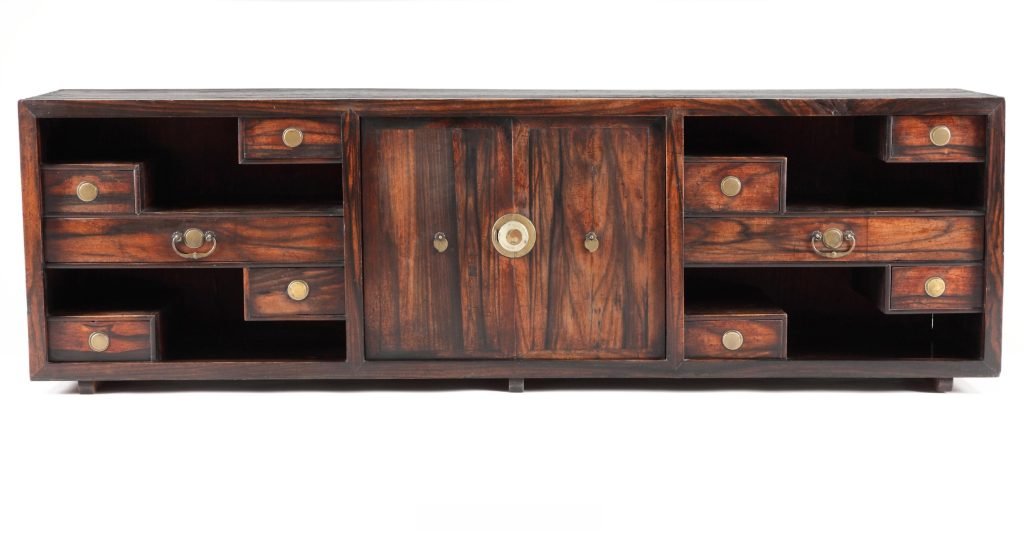

Those small pieces of furniture are called “Mungap”: 문갑 in Korean.

They were used by both men and women to store documents or stationery and were placed in the main room of the house. Documents or stationery were stored inside, and they also served as display stands for brush holders, stones, flower pots, and pottery, which were placed on top.

These chests were typically low and positioned in the space below the window.

The types of “Mungap” are categorized based on their shape. There are single-door “Mungap” (單文匣) and double-door “Mungap” (雙文匣). The “Chaekmungap” (冊文匣) can be used as a small desk. The “Nanmungap” (亂文匣) features multiple open compartments, and the “Dangmungap” (唐文匣) is richly decorated with various floral motifs (花柳文).

Historically, “Mungap” chests were relatively small and tall. However, starting in the late 18th century, their height was reduced to accommodate the practice of living on the floor, and double-door “Mungap” became popular. Typically, a pair of these chests was placed along the room’s wall.

The average height of a “Mungap” chest is approximately 30 cm.

Regarding the wood species, the materials primarily consisted of high-quality timber with a dark stain. Paulownia was a commonly used wood due to its repellent properties and lightweight nature. Persimmon wood, with its two distinct colors (black and light brown), was a popular choice for the front panels. The small doors and drawers were often crafted with a veneer to create a mirror-like effect. Other wood species like red pine, elm, ash, pear, and zelkova were also selected for these pieces.

Some of these chests were adorned with coral, jade, mother-of-pearl, and lacquer.

The National Folk Museum of Korea in Seoul boasts a rich collection of such small chests, and you can find some of them featured in this post.

Colored paper is pasted inside. The Taegeuk pattern is engraved on the front of the leg.

Collection National Folk Museum of Korea.

Legs connected to a cuboid body with one drawer under a rectangular top plate. The bat-shaped decoration has the character ‘卍’ openwork and a key hole.

The surface is painted except for the inside of the drawer and the part where the drawer fits.

Collection National Folk Museum of Korea.

There is a drawer with a bat-shaped handle in the center of each side, and there are small drawers above and below it.

There is a door in the center that can be opened and closed with a padlock.

Although persimmon wood was used throughout, the top and back are made of paulownia wood. Legs are recent.

Collection National Folk Museum of Korea.

4 drawers and 2 storage spaces.

The surface is lacquered.

Collection National Folk Museum of Korea.

Collection National Folk Museum of Korea.

H. 53.4cm, L. 20.0cm, W. 83.0cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Mungap, or stationery chests, were used in master bedrooms or guestrooms to display stationery or interior objects and store important documents or other valuables. This chest contains a secret storage space, a double-tier drawer placed at the middle tier, which can only be accessed by removing the lower drawer, and an upper drawer which can be opened by pushing its outer bottom.

H. 19,3cm, W. 53cm, D. 10,5cm.

Collection of Seoul National University Museum.

H. 36,6cm, W. 75,5cm, D. 25,1cm.

A piece of furniture used to store and store valuable documents or objects. It is a pair of double doors and consists of four doors and three drawers. It is in the form of a double door in which one door is lifted up and removed, and then the other doors are pushed open.

H. 43,8cm, W. 77cm, D. 31cm.

This Mungap is divided into 3 compartments, the bottom compartment contains 3 drawers, the 1st and 2nd tiers have drawers in the center, and the sides are combined to accommodate books or bulky items.

This small chest was used to store documents, stationery, small items, etc. It is a rectangle with six doors. The first door on the left is a double door that can be lifted and removed, and the rest are sliding doors. There is a lock hole in the fourth door. In front of the door, there is a handle ornament with a twist-shaped pattern.

H. 39 cm, W. 55,4cm, D. 39cm.

Early 20th century.

H. 69,7cm, W. 107cm, D. 27,5 cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

H. 45,5cm, W. 88cm, D. 31cm.

Collection: Jeonju University Museum.

H. 29,7cm, W. 78,5cm, D. 45cm.

Collection: Gyeongsangbuk-do Forest Science Museum

A low piece of furniture designed for storing stationery or other items. The upper part is divided into three compartments by joining two pieces of wood at a mitered angle and inserting a drawer into each section. Each drawer features a ‘ㄷ’ shaped latch and a lock attached to the bottom. Inside each drawer, an iron bar is placed, and a swing door is connected at the bottom. The drawers with latches are inserted into the left and right compartments, creating an ‘ㄴ’ shaped storage space. The swing door is equipped with a silver lock. Each drawer and door plate is made of persimmon wood. The side panels of the legs extend to form a plate angle, with a cloud angle attached. Collection: National Folk Museum of Korea.

H. 60cm, W. 82cm, D. 30cm. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

H. 37 cm, W. 83,6 cm, D. 27 cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

H. 32,7cm, W. 105,5 cm, D. 25,4cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

THE INKSTONE TABLE NEXT TO THE DESK.

Scholars would place the inkstone table next to a small desk in order to store various items, including inkstones, ink sticks, and water droppers.

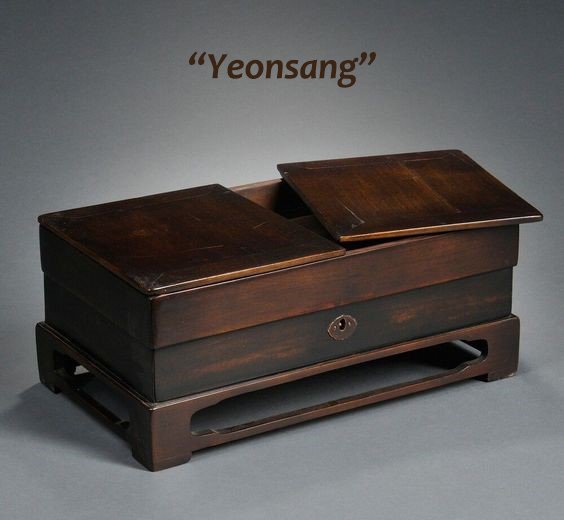

The inkstone box is called “Yeonsang” 연상 硯床 in korean.

“Yeonsang” is a small rectangular box on legs used to collect and organize various small items, such as inkstones, ink, paper, and other documents. This box often features one or several drawers on top and a pedestal underneath. Inkstones and ink are typically stored on the upper part, and the lid is closed when not in use. There is a drawer at the bottom for storing various documents or letters. The stand below is open on all sides and slightly raised from the floor, often with a plank across it to support books, papers, and other items.

The surface of the box is adorned with bamboo pieces cut to a regular size. The top is decorated with the Chinese character “福” (pronounced “bok,” meaning blessing) made of thin bamboo pieces, and glowing patterns adorn the body of the table. Collection: National Museum of Korea.

19th century. H. 22cm, W. 30,7cm, D. 19cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

H. 22,8cm, W. 32cm, D. 18cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Museum of Korea. Seoul.

Most of the stationery items of the Joseon Dynasty were made simply and without any special decorations, reflecting the tastes of scholars.

However, as the economically wealthy class in the late Joseon Dynasty used mother-of-pearl lacquerware, stationery items decorated with mother-of-pearl seem to have become very popular.

This inkstone box is decorated with geometric patterns on the entire surface using the cutting technique. This type of finish was very popular at the end of the Joseon dynasty.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

19th century. H. 31cm, W. 28cm, D. 28cm.

H. 21,4cm, W. 29,4cm, D. 19,9cm.

Collection: Eunpyeong History Hanok Museum. Gyeonggi Do province.

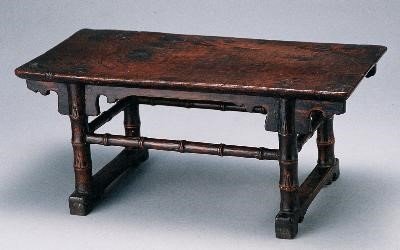

The small desk is called “Seoan” 서안 in korean.

“Seoan (書案)” refers to a low desk used as a piece of furniture for reading or writing support. It was typically situated in the central area of the “Sarangbang“, a space predominantly utilized by men. It is also known as Seosang, Seotak, and Gwean.

The “Seoan” is crafted in a straightforward manner, devoid of elaborate decorations, reflecting the refined and scholarly taste of individuals during the Joseon Dynasty.

Typically, a “Seoan” features a flat top surface for placing books, but there are also variations with both ends rolled up, referred to as “Gyeongsang” (경상) in Korean. Originally, “Gyeongsang” was used as a table for reading Buddhist scriptures in Buddhist temples during the Goryeo Dynasty. In the Joseon Dynasty, it found common use as a writing table. The reason for the rolled-up ends was to prevent scrolls from slipping off when unfolded.

The history of the “Seoan” is not well-documented, and there is a lack of existing data. However, its design can be estimated from the late Goryeo period, as it is depicted in Buddhist paintings. This piece of furniture is also frequently depicted in genre paintings and portraits from the Joseon Dynasty. Early versions typically feature a flat top surface and simple leg design.

H. 27,7cm, W. 51,5cm, D. 31,2cm.

Collection Ilamgwan. Seoul, Korea.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Joseon Dynasty. 19th century. H. 34,7cm, W. 76,3cm, D. 32cm. Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

H. 31,5cm, W. 53,5cm, D. 21,5cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: Korean National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Consists of a top plate, storage compartment and legs. Length: 33

H. 31,5cm, W. 76cm, D. 33cm. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Gyeonggi province. Mid 19th century. H. 34 cm, W.92 cm, D. 41 cm. Collection “ANTIKASIA”

THE DOCUMENT & BOOKCHEST. 책장

Book storage or document chests were crafted for upper-class households, making them relatively scarce and highly prized among collectors of original Korean furniture. These are the largest among scholar’s chests.

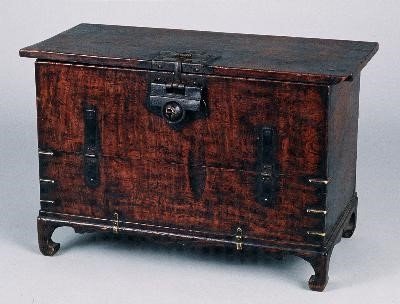

The earliest pieces of furniture designed for the storage of a larger quantity of books or documents seem to be the bandaji, known as 책반닫이 in Korea, which can be translated as “Book bandaji.”

Unlike the basic bandaji used for clothing storage, the Book bandaji typically included an elongated top shelf that extended beyond the furniture’s main structure. Moreover, the cabinet often rested on a more intricate base.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

In the case of other document chests, the earliest examples, dating back to the 18th century, typically featured one or two-level units with double doors on each level. The top shelf, extending beyond the unit’s width, often had raised ends. These chests had finely decorated iron or brass hinges. Additionally, they were supported by cabriole-shaped legs and had a shallower depth compared to other clothing chests, typically measuring around 30 to 35cm on average.

Made of paulownia wood with a slight stain and oil finish, it’s dimension are H. 61cm, W. 75cm, D. 30cm. It is dated 19th century.

The upturned ends on the top panel of this chest indicate that it is a chest for books and manuscript storage rather than for clothes.

Bookchest

This book chest comprises an upper shelf with an open front, while its sides and back are enclosed.

A middle compartment that includes two drawers, and a lower section with a hinged door, forming a cabinet.

The legs of the book chest are adorned with air holes resembling the wings of a bat. Positioned at the center of the door panels is a circular padlock plate adorned with trigram designs. The door panels and the posts are connected by hinges shaped like swallows.

- Culture/Period : Late Joseon dynasty

- Materials: Paulownia & pine wood, yellow brass fittings

Collection National Museum of Korea.

H. 84cm, W. 76cm, D. 27cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Used by the upper class, the two-level carved bookshelf with “Yeouidumun” motifs is a piece of furniture for storing books and scrolls.

H. 113cm, W. 103,8cm, D. 36cm.

Collection Gangwha History Museum, Korea.

H. 114cm, W. 120cm, D. 45cm.

It consists of two levels, with double hinged doors in the center of each level.

There are four engraved characters on each of the eight doors panels, and eight cloud patterns are engraved on the four spaces on the left and right. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

H. 108cm, W. 103cm, D. 45cm. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

H. 117cm, W. 112cm, D. 46,8cm. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

H. 84cm, W. 88cm, D. 25cm. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

H. 103cm, W. 120cm, D. 42,7cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Mid 19th century.

H. 84cm, W. 80cm, D. 32cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

H. 144cm, W. 70cm, D. 28cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

H. 203cm, W. 182cm, D. 76cm.

Collection Songeun Art & Cultural Foundation. Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

H. 171cm, W. 78,5cm, D. 40cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

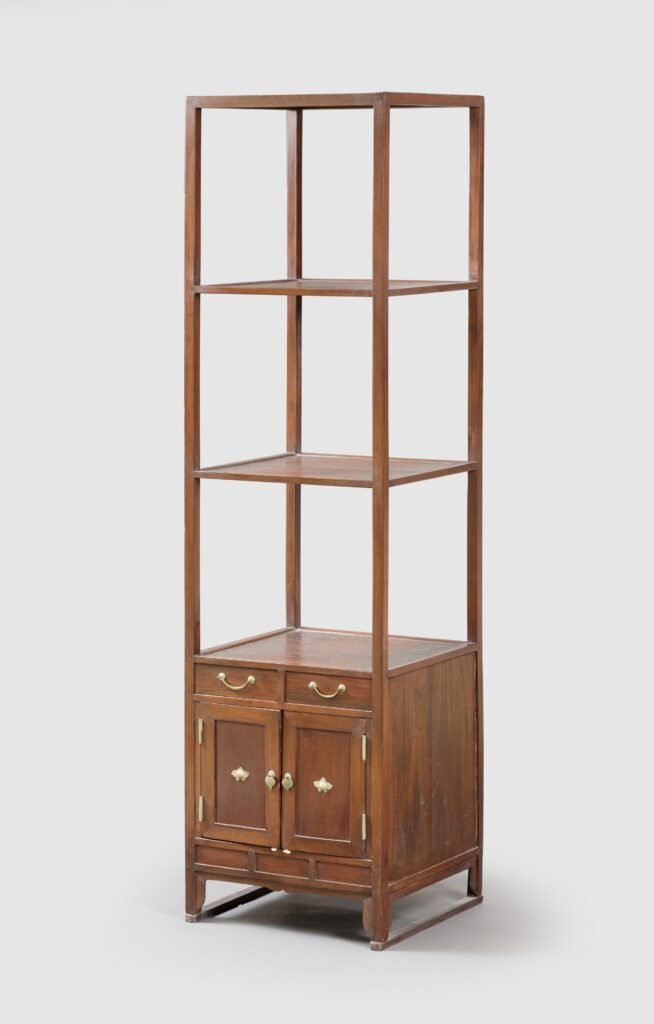

THE BOOKSHELF – 사방탁자

“Open-shelved stands (T’akja) were normally placed next to one or a pair of Mungap and were for displaying pottery and stacking books or manuscripts. They can be of two to five levels, with the bottom level usually enclosed and having double doors.

There seems to be no rule about this, however: the enclosed levels vary rarely, all levels are enclosed. The doors for women’s t’akja are most often of woods with decorative grain such as persimmon, maple, cherry and zelkova. Men’s t’akja are more likely to have a bottom doors of subdued wood grain such as paulownia. T’akja are usually made of three different woods – decorative panels for the doors, a hardwood for the frame (elm) and paulownia for the shelves and sides. The back of an enclosed level might be of still another wood, most probably pine. Metal fittings are of brass or iron.” Edward Reynolds Wright & Man sill Pai KOREAN FURNITURE. Elegance & Tradition.

H. 132,8cm, 34cm x 36,4cm. Collection: National Museum of Korea.

This cabinet consists of two open shelves, where books and stationary items could be displayed, and a lower shelf enclosed with hinged doors, as well as two sets of drawers, where important items could be stored out of sight. The drawers and the hinged doors were made from the wood of a persimmon tree, with the natural black grain symmetrically arranged, highlighting the abstract natural beauty of the wood.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Museum of Korea. (Photos left and right)

ACCESSORIES

It was used as a storage box for storing various documents such as letters, scrolls, and papers, hanging in a room or on the floor. This gobi was made solid with the character ‘卍man’ openwork in the center and bamboo carved pillars on both sides.

National Museum of Korea.

Tajan Auction House, Paris, France. June 12, 2023.

H. 18cm, W. 14cm, D. 14,3cm.

H. 13cm, W. 24,5 cm, D. 11,2cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.