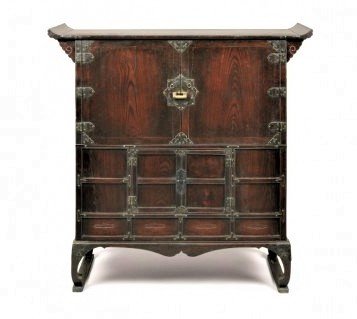

FEATURED PHOTO: From left to right, Chinese wardrobe, Japanese clothing chest, Korean blanket chest.

Korea, Japan, and China share historical and geographical connections. Situated in the northeastern part of Asia, they all share a common trait of being prominent furniture production centers, likely influenced by their climate characterized by four distinct seasons.

Furthermore, these countries have similar beliefs, including religion and philosophy, with Confucianism playing a significant role in regulating the way of life of their inhabitants.

Nevertheless, there are variations in furniture styles, forms, and sizes among these three nations. The objective of this study is to highlight some of these distinctions to make them easily identifiable for those unfamiliar with them.

In this regard, Korean scholars have published excellent papers in two articles that are also accessible on the internet.

- “A Comparative Study on Korean and Japanese Traditional Furniture Design” by Jinok Kim and Choi Kyung Ran.

- “A Comparative Study on Korean and Chinese Traditional Furniture Based on User Patterns” by Ha Jae Kyung and Choi Kyung Ran.

In these two papers, the analysis primarily focuses on the study of the environment, especially the design of houses. We found it intriguing to incorporate elements of the way of life, which, due to their differences, have influenced the distinct designs of Northeast Asian furniture.

To begin, furniture is a reflection of the interior and environment of the region where it is produced. In this respect, Korean and Japanese traditions share similarities, and their furniture commonly features a low sitting lifestyle.

Korean women use wooden beaters to flatten clothing,

c. 1910-1920. Library of Congress Prints and Photos,

Frank and Francis Carpenter Collection.

PHOTO RIGHT.

Japanese lady sitting on the floor.

Space was limited in both Japanese and Korean houses, characterized by low ceilings. Consequently, one can observe the scarcity of large, solid pieces of furniture, except for the Mizuya (kitchen chest) and the Kaidan Tansu (Step chest) in Japan.

FURNITURE TYPES.

Korean furniture can generally be categorized into four main groups:

- Clothing chests (Bandaji, Nong & Jang).

- Kitchen furniture.

- Book chests and shelves.

- Miscellaneous items, including boxes used in the women’s quarters (comb boxes, mirror boxes, sewing boxes, jewelry boxes), as well as those found in the men’s quarters (document boxes, calligraphy sets), and worship furniture like altars, ancestor shrines, and Buddhist sutra desks.

Used to store clothes and various accessories.

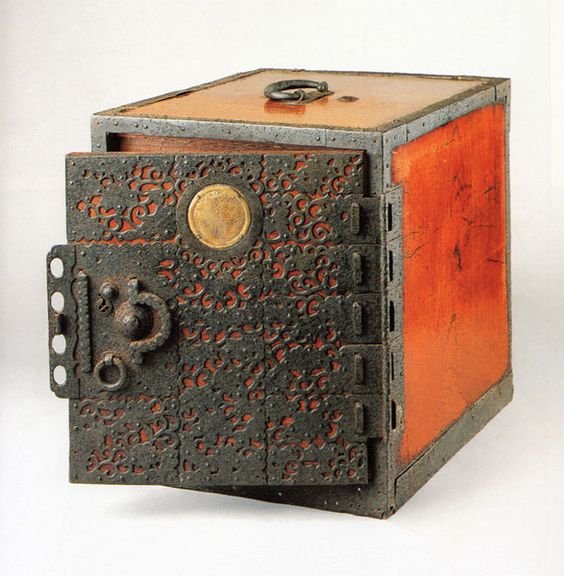

In Japan, in addition to the clothing chests with their numerous long drawers, shelves, and boxes like their Korean neighbors, the typology also includes sea chests (Funa tansu) used on merchant ships. This type of furniture was unique to Japan and not found elsewhere. These chests were relatively small and featured iron openwork plates on their front.

The Kaidan Tansu, known as a Step chest in the west, is another distinctive Japanese design and could be found in shops to provide access to a mezzanine-type floor.

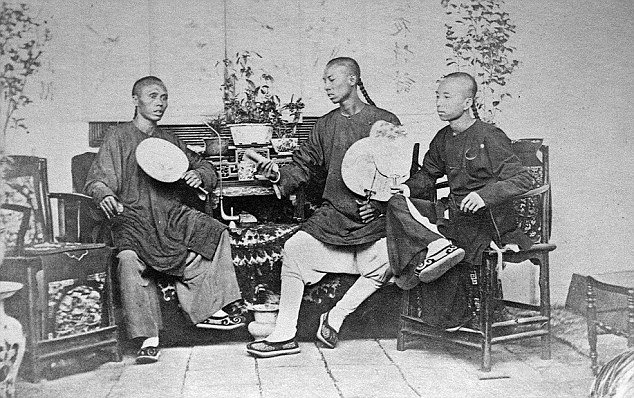

In China the chair was introduced during the Tang dynasty (AD 618 -906). By the end of the Song dynasty (AD 96- 1127), the lifestyle which changed to a standing style reached all levels of the society.

Furniture design differs significantly between Korea and Japan. Wang Shixiang, in “Connoisseurship of Chinese Furniture,” categorizes furniture into five main groups: stools and chairs, tables, couches and beds, cabinets and bookcases, and miscellaneous items.

Chairs, tables, couches, and beds are already relatively uncommon in the Japanese and Korean furniture vocabulary. Due to regional distinctions and differences in the size of the countries, Chinese furniture exhibits a greater diversity of styles.

FORMS AND SIZES:

Korean furniture forms are unique and distinctive.

Some may wonder why Korean furniture is generally of small size. In reality, these dimensions offer insights into the lifestyles of their users. Towards the end of the Joseon dynasty, the average height of men was 161cm, while women averaged 148.9cm, as per data from the Seoul National University College of Medicine. These statistics can be attributed to nutritional conditions, diseases, and other hygiene-related factors.

Additionally, their smaller proportions make them comfortable to view and use from a seated position.

Furniture such as clothing chests was usually small in size. (H x W x D)

Bandaji size : 73-85cm x 90-100cm x 45cm. Morijang size: 75-80cm x 80cm x 40cm.

Nong size: 90-120cm x 80cm x 40cm. Jang size: 140cm x 85cm x 40cm.

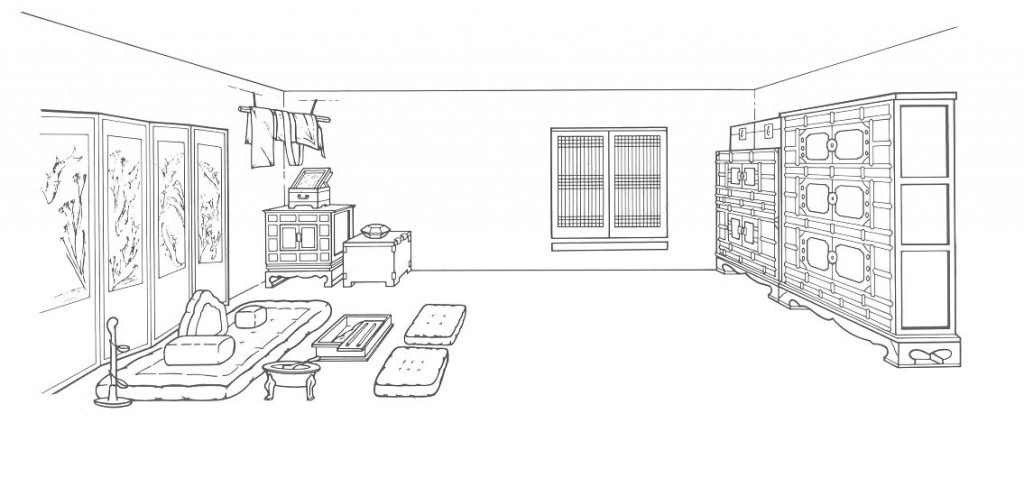

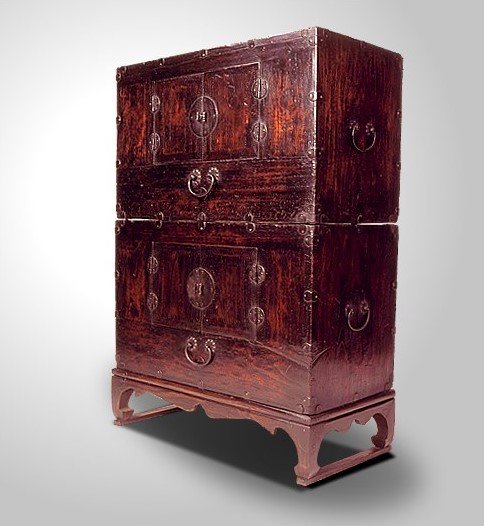

Chests were positioned side by side against the walls to keep the center of the room open, especially in narrow indoor spaces. Consequently, the rear part of Korean furniture was seldom finished with the same level of care as the front. Often, lower-quality wood was used, and at times, no colored finish was applied.

Except for the bandaji (blanket chest), most of the other clothing chests such as Jang & Nong were higher than wider.

Korean clothing, typically consisting of smaller sizes such as a short shirt and pants for men or a small top and a skirt for women, was traditionally folded and stored inside clothing chests. As a result, Koreans developed a distinctive design featuring small doors on the front of these chests. When these doors were opened, the stack of clothes remained stable. Off-season garments were typically placed at the bottom of the stack, while the clothes in regular use could be easily accessed by opening the doors.

Drawers were not commonly used, and when they were present, they were typically quite small, measuring around 15cm x 6cm, and were primarily used for storing small accessories.

Tables and chairs were not typically used, and the dining tray (soban) was stored on top of the kitchen furniture, only being moved when it was time to eat.

Due to the Ondol floor heating system, chests were raised on legs to protect them from the heat. Sometimes objects were placed underneath them.

The leg stands are sometimes separated from the frame of the chests, especially in the case of “Nong,” to make them easier to move. The Cabriole style was the most commonly used, and it was inspired by Chinese design. The bottom frame with legs was crucial for both structural support and protection. This technique was already in use in China at the beginning of the 15th century.

Bandaji chests had two thick boards underneath them to keep them off the floor. Some Bandaji chests from the Gyeonggi area and Pyongyang had more elaborate legs for support.

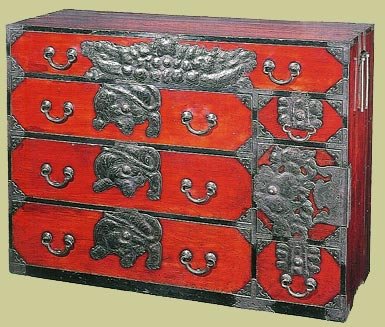

End of the 19th century. H. 82,8cm, W. 90cm, D. 41cm.

Built on elevated legs to protect the chest from the heated floor system.

In Japan, the simple box design was predominant as chests were stacked next to each other.

Furniture became built-in, but it could be easily removed thanks to handles on the sides. The built-in system enabled the production of larger pieces, like the Kaidan Tansu, which is often associated with Korean design.

Chests for clothing storage were wider than they were tall.

Clothing chest used to store kimonos.

Due to the absence of a floor heating system and the tatami mats that covered the floor of the rooms, furniture had no legs and lay flat on the floor. Additionally, fittings were placed on each side for easy transportation.

Unlike Korean chests, the entire front part of a Japanese chest could be used and was divided by long drawers and sometimes sliding doors. This makes it much more practical for today’s lifestyle, as it allowed for the storage of long kimonos laid flat in these drawers.

Drawers covers the entire front of the chest.

The entire front can be open. Combination of drawers and sliding doors.

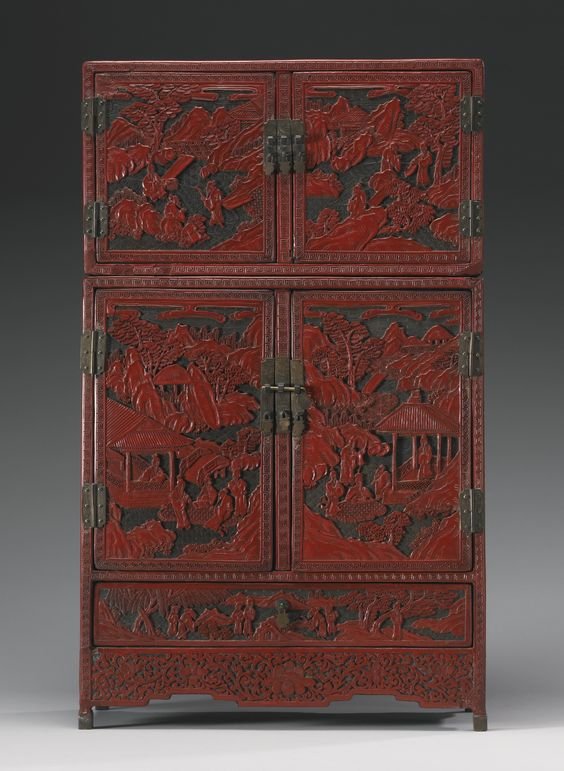

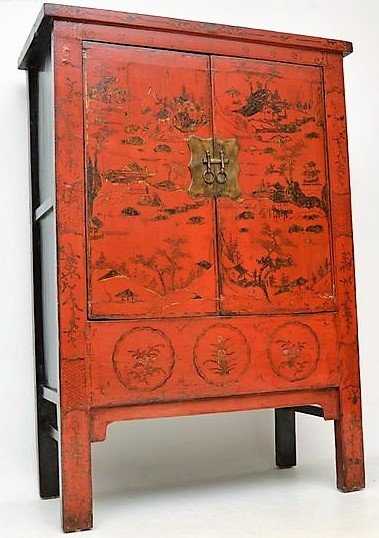

Due to regional differences and the country’s size, Chinese furniture exhibits greater diversity in style. Chinese houses were generally larger with higher ceilings, which led to larger furniture sizes, including tall wardrobes that could accommodate hanging clothes and large sideboards.

Chinese furniture typically features smoother shapes with rounded edges. Most cabinets had removable doors, and the hinged door is a classic feature of Chinese furniture.

MATERIAL & DECORATION:

Popular woods for Korean furniture construction include elm, pine, and paulownia. It was also common for Koreans to use up to 4 or 5 different types of wood on the same chest (Reference: “Korean woods”).

Decoration, such as fittings, inlay, or wood selection, was emphasized on the front of the chest, while the sides and especially the back were left unfinished since they were seldom visible.

Koreans, more than their neighbors, developed the inlay technique. Wood inlay was common on jang and nong furniture, creating striking patterns by using woods of different colors.

On smaller pieces, colored horn and mother of pearl were also applied to the wood surface. When wood was left free of decoration, an oil finish was used to emphasize the grain of the wood.

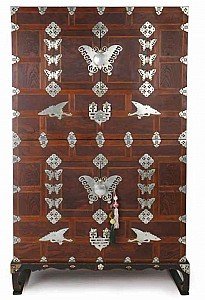

Decorative fittings were made of white or yellow brass on clothing chests. Iron was used for Bandaji and kitchen furniture.

A distinctive classification of furniture was made between the men’s and the women’s quarters. Women’s furniture tends to be more decorated using white or yellow brass fittings with auspicious motives. Lacquered or inlaid pieces were also found in the anbang. Men’s quarter furniture was more sober with dark finishes.

Similar to Korea, Japanese chests were typically placed around the room against the walls. In Japanese furniture, the decoration on the front side was also given emphasis. Cypress, cedar, paulownia, and zelkova have long been the preferred woods for furniture.

Hardware was often used for both functional and decorative purposes, especially on sea chests and clothing chests, particularly those originating from the Sendai province. Iron was a traditional material, and brass and copper were also commonly utilized.

Japanese finishing techniques are, however, different from those of their neighbors in the sense that lacquer was more widely employed.

With the exception of Paulownia tansu, which have a dry finish, the Japanese extensively developed the use of lacquer for furniture finishes.

In the early stages of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), Chinese carpenters utilized the finest hardwoods, such as Huanghuali and Zitan, to craft furniture with simple and elegant designs.

Apart from these rare, imported tropical hardwoods, elm was commonly employed in northern China, while cedar was readily available in the southern regions. Typically, furniture pieces were constructed using a single type of wood.

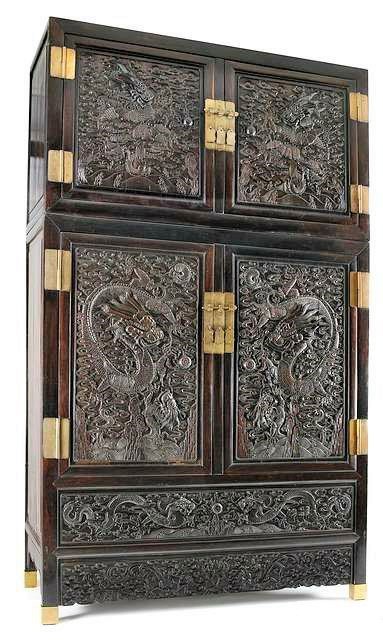

Wood carving, which was relatively scarce in Korea and Japan, gained popularity and widespread development among Chinese carpenters during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Relief and openwork wood carving thrived in the embellishment of cabinets.

PHOTO TOP.

Detail of an Imperial Chinese Zitan Dragon Cabinet, Mid-Qing Dynasty and Later.

PHOTO RIGHT.

Large compound cabinet with intricate woodcarving panels. Nagel Auction.

Metalwork was used at a minimum, usually less for decoration than functionality. It consists of lock plates and drawer pullers.

REFERENCES:

Traditional Japanese Furniture. A definitive Guide. Kazuko Koizumi. Kodansha International. 1986.

Traditional Japanese cabinetry. Tansu. Ty & Kiyoko Heineken. Weatherhill Inc. 1993.

Chinese Furniture. A guide to collecting Antiques. Karen Mazurkewich. Tuttle Publishing 2006

Chinese furniture. Selected articles from Orientations 1984-2003.

Connoisseurship of Chinese furniture. Ming and early Qing Dynasties. Wang Shixiang. Art Media Resources Ltd. 1990.

Another interesting publication about Asian furniture which enable you to compare furniture styles by countries of origin.

I would like to have someone give me an estimate of cost to come appraise furniture.

Send us photos to: tortuebangkok@gmail.com.